Viewing History and Changes#

Learning objectives#

Understand how to view the history of commits in a Git repository using the

git logcommandLearn to navigate through the log output using the paging commands

Use the

gif diffcommand to view differences between commits and changes in the working directoryDifferentiate between various states of changes: unstaged, staged and committed

Explore GUI tools for viewing differences in files

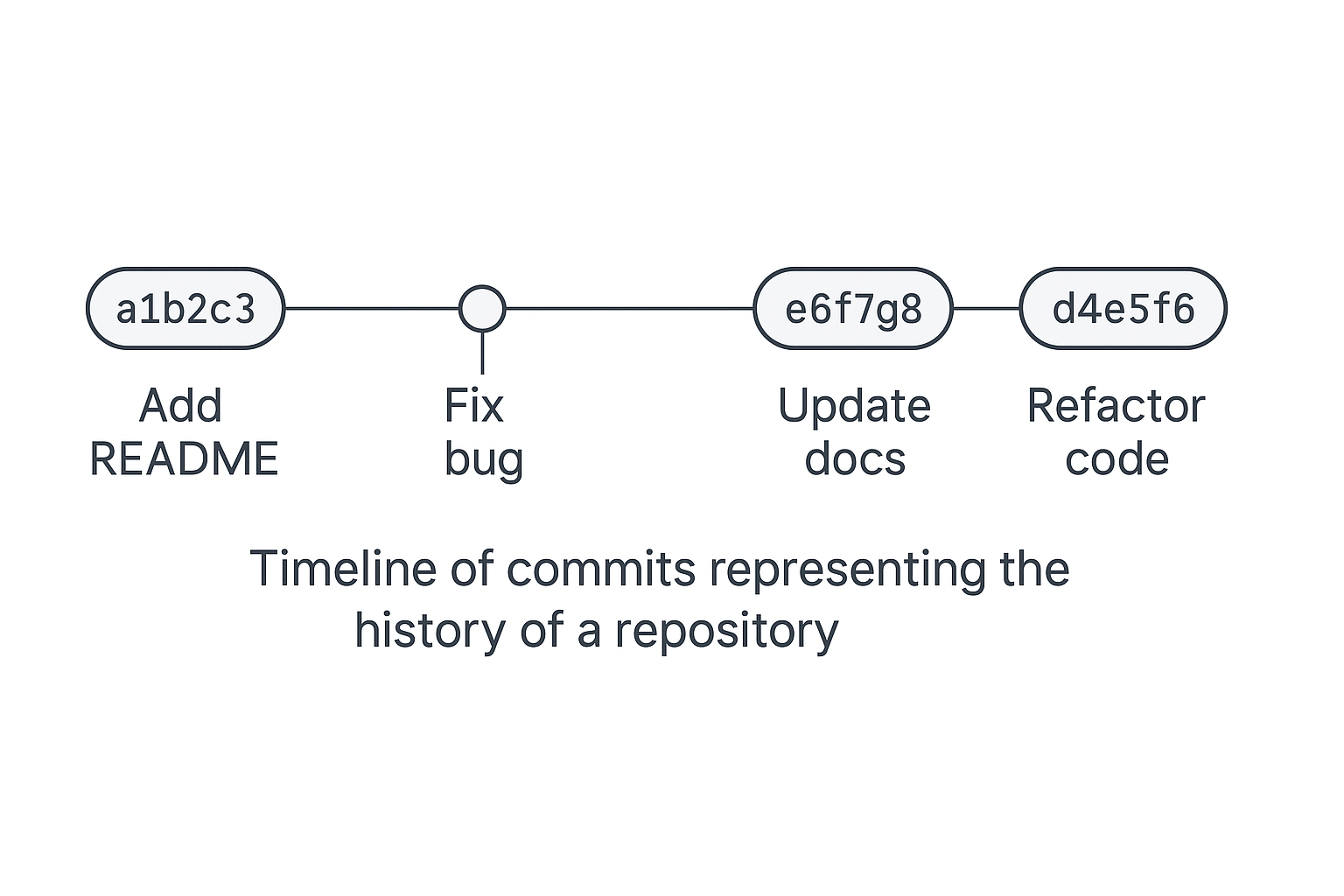

Viewing repository history#

There’s little point in keeping a history of changes to files in a repository if

we can’t view it. We can view a record of the commits made in a repository using

the git log command. If you completed the exercise at the end of the last

episode, Recording Changes, then

running git log from within the git-good-practice repository should look

something like the following:

commit 46b11e612128e68a9d558be1bcaa82bbdaac34ab (HEAD -> main)

Author: Joe Bloggs <joe.bloggs@example.net>

Date: Tue Feb 7 16:47:21 2023 +0000

Add advice on committing little and often

commit ecbf67e161e805a3183ebc84eb7d39c229a78451

Author: Joe Bloggs <joe.bloggs@example.net>

Date: Tue Feb 7 16:46:54 2023 +0000

Add entry for 'git commit' with '-m' option

commit 34c19f2dd01c42fa2981520ca436bde5378979cb

Author: Joe Bloggs <joe.bloggs@example.net>

Date: Tue Feb 7 16:14:14 2023 +0000

Add material on committing

This includes both an entry for 'git commit' in the cheatsheet

and also material on good practice for commit messages in a new

'good practice' document.

commit ad56194133fcac4f65d236260f372665fbec605b

Author: Joe Bloggs <joe.bloggs@example.net>

:

Paging the Log#

When the output of git log is too long to fit in your screen, Git uses a program called a pager to split it into pages of the size of your screen. When this pager is called, you will notice that the last line in your screen is a :, instead of your usual prompt.

To get out of the pager, press Q.

To move to the next page, press Spacebar.

To search for

some_wordin all pages, press / and typesome_word. Navigate through matches pressing N.

The log contains one entry for each commit. The commit messages for the commits are included, as well as details of who made the commit. The name and email address are those that were given when configuring Git (see the episode Setting up Git and GitHub).

In addition, each commit has a unique identifier associated to it, which is the long random-looking string next to each commit. (The identifiers for your commits may differ from those above.) We can refer to commits by their identifiers within Git. As we’ll shortly see, commits can also be identified via their short identifier, which is just the first 7 characters of the usual identifier.

Git also has a way of referring to the current, or most recent, commit: this is

called HEAD. In the above output, HEAD refers to the commit with message

“Add advice on committing little and often” (as indicated by (HEAD -> main)).

Limiting log output#

To avoid having git log cover your entire terminal screen, you can limit the

number of commits that Git lists by using -n, where n is the number of

commits that you want to view. For example, if you only want information from

the last commit you can use git log -1:

$ git log -1

commit 46b11e612128e68a9d558be1bcaa82bbdaac34ab (HEAD -> main)

Author: Joe Bloggs <joe.bloggs@example.net>

Date: Tue Feb 7 16:47:21 2023 +0000

Add advice on committing little and often

You can also reduce the quantity of information using the --oneline option:

$ git log --oneline

46b11e6 (HEAD -> main) Add advice on committing little and often

ecbf67e Add entry for 'git commit' with '-m' option

34c19f2 Add material on committing

ad56194 Add entry about staging files with 'git add'

17912ce Create a cheatsheet document

3917168 (origin/main, origin/HEAD) Initial commit

Note that, in this format, each commit has its short identifier displayed.

You can also combine the --oneline option with others. For example, to view

just the last 3 log entries on single lines:

$ git log --oneline -3

46b11e6 (HEAD -> main) Add advice on committing little and often

ecbf67e Add entry for 'git commit' with '-m' option

34c19f2 Add material on committing

git diff: viewing changes#

One of the key features of Git is being able to see the changes that

have been made to files when working in a Git repository, not just a record of

the commits. The git diff command gives us access to this information.

Like many Git commands, git diff can take arguments in several different

formats, depending on things like the optional arguments used. We’ll focus on

two basic use cases of git diff, considering various shortcut forms along the

way:

git diff <commit1> <commit2> <files>for viewing differences in files between particular commits.git diff <files>andgit diff --staged <files>for viewing changes to files that have yet to be staged or, in the second form, yet to be committed.

Differences between commits#

Let’s first look at how to examine file changes that have been made to go from one commit to another. The general form of the command to do this is:

git diff <commit1> <commit2> <files>

Commits should be referred to by their identifiers (either their normal or short

formats). The order that the commits are specified matters: in the above, the

output will describe the changes that need to be applied to <commit1> to get

<commit2>. The <files> argument can be a single file or list of multiple

files.

As an example, based on the full one-line log given above, let’s look at the

changes required to go from commit

ad56194 (with message “Add entry about staging files with ‘git add’”) to commit

34c19f2 (with message “Add material on committing”), for each of the files

Git-cheatsheet.md and Commit-good-practice.md:

$ git diff ad56194 34c19f2 Git-cheatsheet.md Commit-good-practice.md

diff --git a/Commit-good-practice.md b/Commit-good-practice.md

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..9610409

--- /dev/null

+++ b/Commit-good-practice.md

@@ -0,0 +1,12 @@

+# Best practice when committing

+

+## Commit messages

+

+[Chris Beams: How to Write a Git Commit Message](https://chris.beams.io/posts/git-commit/)

+start with a brief (usually < 50 characters) summary statement about the

+changes made in the commit, with more explanation given in a new paragraph if

+required. Generally, the summary should complete the sentence "If applied, this

+commit will [_commit message here_]".

+

+Avoid uninformative messages such as "small tweaks" or "updates" — write what

+will be useful for others to read.

diff --git a/Git-cheatsheet.md b/Git-cheatsheet.md

index c2409dd..26bcb5c 100644

--- a/Git-cheatsheet.md

+++ b/Git-cheatsheet.md

@@ -11,3 +11,6 @@

## Adding / committing changes

`git add <files>` — Stages changes in the `<files>`, ready for committing.

+

+`git commit` — Commit changes to the repository that have been staged with

+ `git add`.

The output describes the differences (or diffs) of each file between the versions in the specified commits.

Understanding the output of git diff#

The output of git diff, as shown above, is cryptic because it is actually a series of commands for tools like editors and patch telling them how to reconstruct one file given the other. If we break it down into pieces:

The ‘diff’ for each file begins with a line like

diff --git a/<filename> b/<filename>. It tells us that Git is producing output similar to the Unixdiffcommand, comparing the old and new versions of the file<filename>. In the example above, the output starts with the diff forCommit-good-practice.mduntil just before the linediff --git a/Git-cheatsheet.md b/Git-cheatsheet.md, at which point it switches to the diff forGit-cheatsheet.md.The next few lines in each file’s diff tell exactly which versions of the file Git is comparing. Confusingly, it looks like it contains commit identifiers, but these are in fact different, computer-generated labels for the versions of the files.

The remaining lines, beginning

@@, are the most interesting: they show us the actual differences and the lines on which they occur. In particular, the+marker in the first column shows where we added a line. If we had lines that were removed, these would be marked with-.

If we wanted to view just the diff for the file Git-cheatsheet.md we would

supply that as the only file argument, like so:

$ git diff ad56194 34c19f2 Git-cheatsheet.md

If we leave out <files> altogether, then Git will show the diffs for all files

that were changed in the given commits. With the commits ad56194 and 34c19f2

above we only have the two files, so in this case

git diff ad56194 34c19f2

would give the same output as git diff ad56194 34c19f2 Git-cheatsheet.md Commit-good-practice.md.

Sometimes you only want to see which files have changed between commits. This

can be achieved with the --name-only option:

$ git diff --name-only ad56194 34c19f2

Commit-good-practice.md

Git-cheatsheet.md

If we just want to compare the latest commit — that is, the commit referred to

by HEAD — with a previous commit, we just provide an identifier for the

commit to compare to:

git diff <commit> <files>

The rules for <files> are the same as before. For example, to view the changes

to the file Commit-good-practice.md from commit 34c19f2

(“Add material on committing”) to the latest commit:

$ git diff 34c19f2 Commit-good-practice.md

diff --git a/Commit-good-practice.md b/Commit-good-practice.md

index 9610409..524d4ec 100644

--- a/Commit-good-practice.md

+++ b/Commit-good-practice.md

@@ -10,3 +10,14 @@ commit will [_commit message here_]".

Avoid uninformative messages such as "small tweaks" or "updates" — write what

will be useful for others to read.

+

+

+## Commit little and often

+

+Aim for each commit to capture one conceptual change to your work that

+can stand alone. This will make the history of your files' development much easier

+to follow.

+

+A good rule of thumb: a commit should capture a change that

+you can describe in about 50 characters or fewer, potentially with extra

+explanation in the commit message if needed.

Using your HEAD#

The case where you want to compare the most recent commit to an earlier one in

the history especially common. Git provides some syntax to refer

to commits relative to the current HEAD commit. We can refer to the commit that is

n commits before HEAD with HEAD~n (think HEAD minus n steps). These

are just more convenient ways to refer to commits and so can be used instead of

the identifiers we’ve been using so far. Let’s look at some concrete examples,

using our git log --oneline output from earlier:

The command

git diff HEAD~1would give the file changes applied in the most recent commit (i.e. to go fromHEAD~1toHEAD). This is just the changes made in commit46b11e6(with message “Add advice on committing little and often”).The command

git diff HEAD~3 Git-cheatsheet.mdwould give the aggregate changes that have been made toGit-cheatsheet.mdsince commitad56194i.e. the changes required to go from 3 commits earlier to the current commit.The command

git diff HEAD~3 HEAD~2would give the changes required to get from commitHEAD~3(ad56194) toHEAD~2(34c19f2). In other words, it just gives the changes applied back when we did commit34c19f2.

Exercise#

Verify the claims in the three bullet point examples given above, checking the outputs of git diff agree for the HEAD versions and the regular commit identifier versions. Note: make sure to use the commit identifiers found in your own log, not the ones that feature in the example output above!

Working tree and staging area diffs#

It is good practice to check exactly what you are going to commit before you

do so, especially if you have been working on multiple files simultaneously.

We can use git diff to examine changes to files that have yet to be staged

or committed.

Changes that have not been staged#

Let’s suppose we add some new content to our cheatsheet about git log:

## Viewing repository history

`git log` — Shows the history of commits that have been made.

`git log --oneline` — Show summary commit information, one commit per line.

This will add changes to the working tree for our repository. We can view the

diff for changes that are in the working tree, but have not yet been staged,

by using diff without reference to any commits:

git diff <files>

As usual, we can leave <files> empty and Git will return the diffs for all

files that have changed.

Running this in our git-good-practice repository now yields

$ git diff

diff --git a/Git-cheatsheet.md b/Git-cheatsheet.md

index 135822a..86e679f 100644

--- a/Git-cheatsheet.md

+++ b/Git-cheatsheet.md

@@ -17,3 +17,10 @@

`git commit -m "commit message here" — Commit changes to the repository, using

the given commit message

+

+

+## Viewing repository history

+

+`git log` — Shows the history of commits that have been made.

+

+`git log --oneline` — Show summary commit information, one commit per line.

as we would expect.

Changes staged, but not committed#

Suppose we now stage the changes above made in the previous section and run

git diff again:

$ git add Git-cheatsheet.md

$ git diff

$

No output is returned because the default

behaviour of git diff is to show changes that are in the working tree but

have not been staged. We can use the --staged option to view the changes that

have been staged, but not yet committed:

$ git diff --staged

diff --git a/Git-cheatsheet.md b/Git-cheatsheet.md

index 135822a..86e679f 100644

--- a/Git-cheatsheet.md

+++ b/Git-cheatsheet.md

@@ -17,3 +17,10 @@

`git commit -m "commit message here" — Commit changes to the repository, using

the given commit message

+

+

+## Viewing repository history

+

+`git log` — Shows the history of commits that have been made.

+

+`git log --oneline` — Show summary commit information, one commit per line.

Exercise#

First follow the steps above, so that you end up with entries about git log and git log --oneline in Git-cheatsheet.md that are staged but not committed.Now add a new entry to the cheatsheet about git log -n, but don’t stage it. Next do the following:

Run

git diff Git-cheatsheet.mdRun

git statusCan you explain what the output from these commands is saying, and why we get it? Once you’re happy you understand what’s going on, complete the task of adding the material aboutgit logto the cheatsheet by making an appropriate commit, making sure to include the entry aboutgit log -n.

Viewing diffs with GUIs#

We appreciate that the output of git diff is not the most intuitive

way to view differences between file versions. Fortunately, many text editors

and IDEs support ways of visually depicting differences, either ‘out of the box’

or through the installation of a plug-in / extension. Do a search online

to see if this is the case for your preferred text editor / IDE.

VS Code#

For VS Code users, the following links may be of help:

View the diffs for files that have not been staged, or have been staged but not committed https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/sourcecontrol/overview#_working-in-a-git-repository.

View the commit history of a file: https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/sourcecontrol/overview#_timeline-view. This also suggests some extensions for VS Code to make working with Git more graphical.

Displaying diffs by selecting files to compare: https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/sourcecontrol/overview#_viewing-diffs. Note that the method described in this link can be used on the ‘timeline’ described in the previous link: simply right-click on different commits in the timeline for a given file to see the changes between the commits.